Fire Forecast for the Summer of 2025

The Summer I Turned Pretty Existential

by Tim Berenyi

When people ask me what my favourite season is, without hesitation I say Winter and when pressed for a reason I say oh you know because it’s my birthday, the footy is on, and it snows.

But the truth is, I hate summer because I’ve always been scared of bushfires.

I was born in 1994 and my earliest memories are of running around the muddy paddocks playing in the overflow from the dams. I remember rain falling in thick sheets for days at a time.

Then in 2001 the Millennium Drought started and by 2002 the El Niño weather pattern had super charged the conditions - at the time it was Australia’s forth-driest year since 1900. Rainfall remained below average until early 2005.

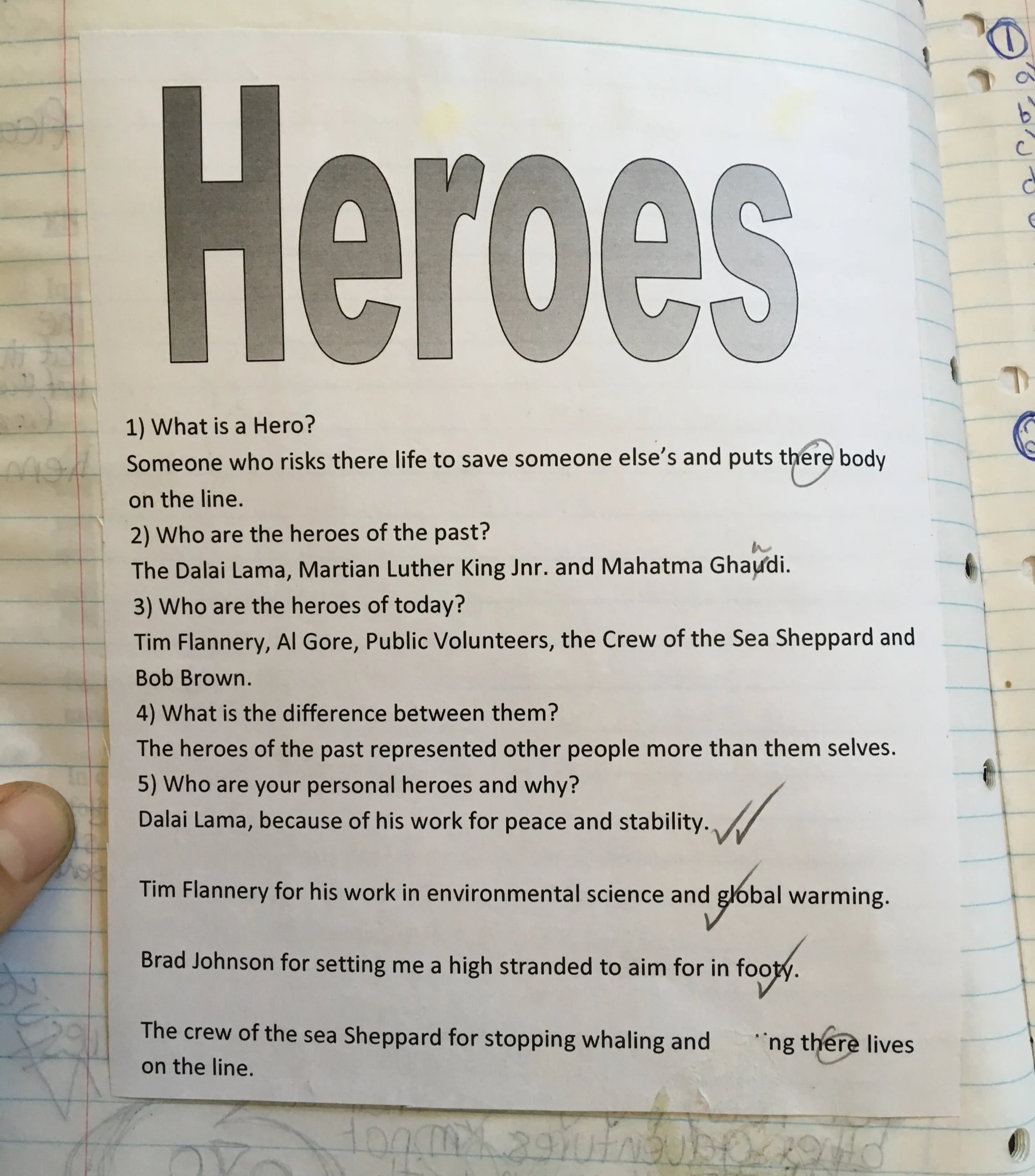

But by 2006, Victoria experienced it’s second driest year on record since 1900. I was in grade 6, just finishing primary school. Not long ago I found a note book in the shed which listed my heroes at the time: Brad Johnson, as captain of the Western Bulldogs; the Dalai Lama, for his work on peace; and Professor Tim Flannery for his work on climate change.

Because even back then I could tell things had changed: where had the flooding rains of my childhood gone? Those memories felt more like a dream than reality.

In 2006, there were huge fires in the Victorian Alpine region - where I grew up. My Aunty and Uncle live on top of a hill from where you get an unobstructed visa of Mt Buller and the surrounding ranges. Such a good spot to live. I remember being up there on a balmy night in late December for my cousin’s birthday and we spent most of the night on my Uncle’s telescope taking turns to watch the fire spread up the mountains like a big glowing snake.

A week later, on Christmas Day, it started snowing. The season’s pass for Mt Buller that year had a photo of a fire truck covered in snow with a finger written Thank You on the windscreen.

The crisis was averted, and everyone went back to their business. I distinctly remember thinking how bizarre it was that everyone just went back to normal. After months of living with thick smoke blanketing everything and an emergency bag packed on the back of the door, everyone just went back to as things were before. But here I was, washing everything I owned to try to get the smell of smoke off them.

Just the smell of the smoke would bring me back to the hot sleepless nights, worrying about how many trees, and insects, and other creatures had no where to go. No one seemed to care, but I felt as though I could feel their pain.

Those summer nights were torment. But the fires went out and people moved on.

A couple of years later, it’s 2008 - I’m 14 and now living more with my head than my heart, as is the sad reality of ‘becoming a man’, which I thought at the time meant not having any feelings, especially ones you would share. I spent a lot of that summer around at the Country Club across the lake that a mate’s family was managing so he lived on site. Not one of those joints from the movies with rolling green lawns and people in chinos, think more big school camp with people in trackies and patches of verdant green where things were leaking. I would ride my bike across the empty lake bed and we’d sneak into the pool area to cover ourselves with olive oil trying to get a tan, followed by seeing who could stay in the sauna without drinking any water. You know, typical teenage boy stuff.

I remember that summer being painfully hot, which the persistent sun burn didn’t help. I was playing cricket, a game that involves a lot of standing in the sun. On one Saturday in early Februrary it was really, really hot. There was a strong breeze that made it feel empathy for a chip in a fan forced oven. I can remember thinking as I stood in the outfield, I think this is the last game of cricket I’m going to play - what a dumb idea it is to stand in a paddock under the searing sun.

The game ended early because of the weather was forecasted to turn wild and by 11am I was home in the pool.

We had a 10 metre in ground pool, which was the coolest thing we had - even though our house was allegedly only about 300 metres or so from Lake Eildon, on the Burnt Creek Inlet. I say allegedly because I honestly didn’t believe my parents when they said there should be water at the end of that paddock. All I knew the lake as was the big open dry space where we could do anything. Ride horses, make bike jumps, fang motorbikes, had mud wars, and occasionally spear some carp as they thrashed about in the mud.

Looking back, a pretty idyllic childhood - freedom to do anything, except splash in puddles.

So there I was in our pool, trying to set the Howes Creek record for the most laps underwater with a single breath (16 laps that day - now I struggle to get 3). I remember seeing the smoke start to come over from the south-west, as the crow flies not far from the town of Eildon and beyond that Marysville, a tiny town in the forest with an unreal lolly shop, an amazing sculpture garden, and the coolest ground in the league surrounded by huge gum trees on all sides - felt like you were playing in a fairy tale.

As the smell of smoke got stronger, that feeling from just a couple of summers came back - a deep sense of foreboding.

As the sun went down I got out of the pool and went inside. The rest of my family were sitting in silence watching the 7:00pm ABC News. On the screen was images of flashing lights, convoys of fire trucks, and people in uniforms with stern faces giving speeches infront of a line of microphones. One of my sisters was visiting from Melbourne and she was freaking out. I remember thinking jeez she’s not handling this well, but she’s a city slicker and wasn’t here in 2006 to see how bad those fires were.

I wandered off to bed after getting yelled at for making jokes about the fire. But in my room I couldn’t sleep. Tears filled my eyes, I blamed the smoke.

When I woke the next morning, I could hear the TV on in the lounge room which never ever happened. Bleary eyed I went in, the same scene was in front of me - Mum on a sofa, Dad standing, one sister laying on the floor, the other literally on the edge of their seat.

I looked at the TV, it was a rolling shot taken from a helicopter looking down on a grey landscape. Every so often a huge explosion would contrast the monochromatic image with a burst of intense oranges and yellows. All the trees were black. Like looking at a box of matches that had all been lit at the same time. Then it passed over a footy oval. It looked so familiar.

Dad turned to me and confirmed my fears: “Yep, that’s Marysville right now.”

Suddenly the jokes from last night made me feel sick.

This was way worse than 2006. There’s no way it’s snowing now. It was the 7th of February, later to be known as Black Saturday. Over 400 separate fires started that day, 173 people died.

A week before the fires, South-Eastern Australia experienced a significant heatwave. From 28 to 30 January, Melbourne broke temperature records by experiencing three consecutive days above 43°C, with the temperature peaking at 45.1°C on 30 January - the third hottest day in the city's history. A week later several localities across the state recorded their highest temperatures since records began in 1859, with the highest on Black Saturday.

Those fires burnt for the next month and it wasn’t until mid-March that the fires finally went out.

It was then I realised my life would be demarcated by record breaking events.

Since I was born in 1994, southern Australia has experienced below-average rainfall for 25 of the last 31 years. Since I was at university, 10 of the hottest years on record have all occurred within that decade (2015-2024) - I was 21 in 2015.

Then in 2016, the weather finally shifted. La Niña conditions arrived, and the rains returned. Not quite the blanket rain of my childhood, but thick flooding rain. All of a sudden the lake was full, and I finally believed my parents.

Everything became a verdant green. Everyone’s moods shifted, things weren’t so bleak anymore. Summer holidays were fun, life was rejuvenated. And I thought, why the heck did you spend so much time worrying about how bad these would get?

Everyone else has forgotten so why haven’t I?

My family has lived in the same areas since 1854, coming to Bonnie Doon as poor Irish Catholics creating a life on the frontier. A history I am not proud of, but with the context of history and English imperialism I can understand why. But the blood runs deep in the hills. I’m now the 6th generation born in the same town, which not many people have.

Except of course the people who were here First. I always thought I was being a bit woo-woo when I would say I have an emotional connection to the landscape, I feel a deep respect for it and an even deeper drive to keep it healthy. No one growing up could ever relate, and even less could when I moved to Melbourne for university.

So I ignored those feelings and didn’t tell anyone, until I started working with mob in the Northern Territory. Everyone there completely understood - on a level I could never comprehend. If I feel like this after just 6 generations, what it must feel like after 2,000 - 3,000 generations. That blood doesn’t just run deep, that blood is the landscape.

By mid 2019, the rains had stopped again. Things were lush, but water wasn’t abundant like it had been.

I had just returned to university to study a masters of environmental governance, policy, and markets in an effort to better understand what decisions had been made in the past that were effecting the present and the future.

Melbourne is a very expensive place to live, but I suppose that is true of most cities - from the moment you open your door it’ll cost you: be that a public transport ticket, parking lot entry fee, or getting fined for criminal behaviour like not wearing a helmet.

So I used to go back home to work most summers, work is easy to come by but it’s never easy work. That summer I had decided to apply to work on the Summer Crew with the Department of Changing Names (aka DELWP at the time, and DEECA nowadays). We started second week of November and were straight into training which for first year’s involves a week long camp where you learn the general fire fighter skills you need for the job - fire behaviour theory, pump operations, practicing rakehoe lines.

Before the week had concluded we were already getting calls telling us to be prepared for deployment to a fire as soon as we got back, and it was likely to be night shifts. We were all nervous, but also a bit excited.

By the end of the summer that excitement had well and truly evaporated - and at one point when there was almost one continuous fire from my home in North East Victoria all the way to the North of Sydney. Half of the Great Dividing Range had burnt and I thought I might never be able to go back to Melbourne.

Then before utter catastrophe the rains finally came. I can still remember the moment, we were having crew dinner at one of the local pubs and someone came running in completely drenched shouting “it’s flooding!”

And once again, everyone moved on. No one wanted to talk about it. Everyone forgot.

Those fires would come to be known as the “Black Summer Bushfires” that burnt an area about the size of Mexico (~24 million hectares), 33 people died directly from the fires and another 455 died from smoke inhalation, over 3000 houses lost, and an estimated 1 billion animals perished.

Unlike Ash Wednesday or Black Saturday, the fires were so widespread, so intense, and went for so long that the entire summer has a name.

What will the next be called? Just Summer?

Even as I write this on October 22 it is raining. And most people will think, oh it rained yesterday so it’s not that dry at the moment - despite it only raining for about 20 minutes for the entire day. Don’t you remember when it used to rain for a whole day? The cognitive dissonance will always amaze me.

The build up to this summer is feeling eerily similar to 2019.

That year was marked by exceptionally dry conditions on the East Coast, a lack of soil moisture, and fires started in Central Queensland during June.

This year, 2025, there has been particularly dry conditions in Southern and Eastern regions due to low rainfall throughout winter and early spring, concerningly low soil moistures, and fires have started in Central Queensland and Eastern South Australia.

Before we conclude - yes, there have always been bushfires in Australia, but the difference how regular they are now and how much bigger they’ve become. Before the 90s, forest fires were intense but infrequent - a given area would burn every 20 to 100 years. Huge events were rare, such as the fires of 1939 - but even then only a small fraction of the total forest area burned in a given year.

But since 2002, this trend no longer exists.

We’re now in a period where we’re experiencing things that have not occurred before. Currently there is one of the strongest negative Indian Ocean Dipoles (IOD) on record, combined with a developing La Niña, and ongoing record high warm waters around Australia suggest that should be seeing widespread rain. However, at the same time these wet influences are up against a sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) event high above Antarctica, which heavily favours dry and warm conditions.

This confluence of weather systems is a scary prospect for fires as a majority are lit from lightning strikes as storms roll across the landscape. The difference now compared to the past is that storms used to also bring rainfall - but in recent years the clouds comes but not the rain.

The major thing is most of us are not able to comprehend is the compounding effect these dry years are having. Especially when for most of us, it is all we have ever known.

The time to act was yesterday, the time to start is now.

By Tim Berenyi